Warhol, Prince, and The Supreme Court Examine Limits of Art and Creativity in Copyright Law Dispute

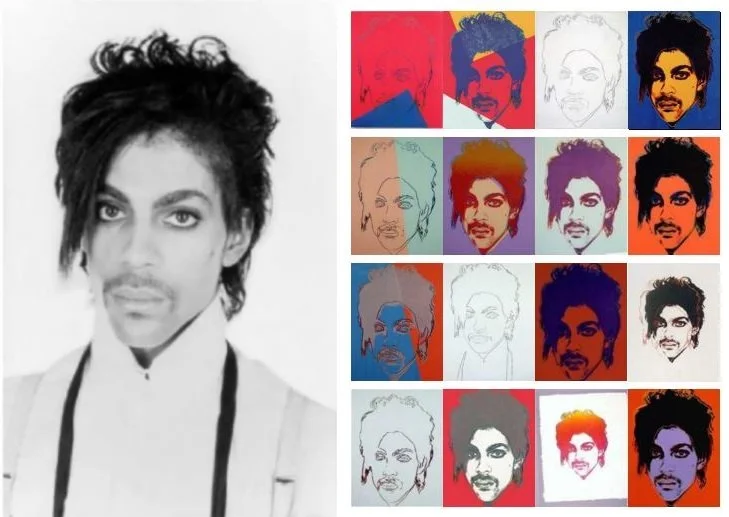

Lynn Goldsmith’s photo of Prince (left) and the series of prints created by Andy Warhol (right). Images taken from Petitioner’s brief filed with the United States Supreme Court.

In October 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. The case is centered on a series of prints of the musical artist Prince by renowned pop-art artist Andy Warhol and what it means for a derivative work to be transformative of its original. The prints were based on a photograph by Lynn Goldsmith which was licensed by the publisher Condé Nast for its magazine Vanity Fair. Warhol used the Goldsmith photo as a reference. While the Goldsmith photo was black and white and featured Prince’s shoulders, Warhol cropped and colorized the prints using just Prince’s head. Goldsmith received co-credit for the illustration. Upon Warhol’s death, the prints and their copyrights were given to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Litigation History

Following Prince’s death in 2016, Condé Nast published a commemorative magazine looking back on Prince’s life and included one of the Warhol prints as the cover image. Condé Nast credited the Warhol Foundation but not Goldsmith. This was brought to the attention of Goldsmith who alleged to have no knowledge of the Warhol prints despite the licensing and co-credit thirty years prior. Goldsmith told the Warhol foundation that she believed the Warhol prints were copyright violations of her original photograph. In response, the Warhol Foundation filed for a preliminary ruling in the Southern District of New York. The Foundation was successful and the District Court granted a motion to block further action from Goldsmith. The District Court’s reasoning was that Warhol had transformed Goldsmith’s original photograph under fair use to show the change of Prince “from a vulnerable uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

Goldsmith appealed to the Second Circuit which reversed the District Court’s decision and allowed Goldsmith to continue her lawsuit. The Second Circuit stated that the District Court erred in that it “should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue. That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.” Furthermore, it was clear that Warhol prints derived from Goldsmith’s photograph and that they “[retain] the essential elements of the Goldsmith photograph without significantly adding or altering those elements.”

Following the Second Circuit’s ruling, the Warhol Foundation petitioned the case to the U.S. Supreme Court stating that the Circuit Court’s ruling was a marked change in copyright law and would increase legal uncertainty for others in the arts. Warhol’s work falls under a type of fair use known as “transformative use.” It further argued that taking such a position would create a chilling effect whereby other artists would be disincentivized from creating similar works in fear of possible infringement claims. Goldsmith argues that the Warhol Foundation is being hyperbolic, alarmist and relying on a slippery slope.

The Issue - “Transformative” Fair Use

In U.S. copyright law, fair use is a doctrine whereby use of a copyrighted material is permitted. One such type of fair use is “transformative” fair use. Transformative fair use is where a creator builds upon a preexisting copyrighted work and significantly changes its appearance or nature.

The Supreme Court examined the meaning of transformative fair use in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music regarding 2 Live Crew’s song “Pretty Woman” which was based on the Roy Orbison song of the same name. The Court ruled in favor of 2 Live Crew stating that their version of “Pretty Woman” was a “parody” of the Orbison song’s wholesomeness and naivete. The test prescribed in Campbell for whether a work is transformative and not infringing on the original’s copyright is whether it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.”

The question then is whether added meaning or context (e.g., showing Prince as an iconic, larger-than-life figure) makes the Warhol prints transformative for copyright purposes. The Warhol Foundation asserts that Goldsmith’s photo shows a “fragile and vulnerable” Prince. He is a person like anyone else. Meanwhile Warhol’s prints dehumanize him and show him as a celebrity. Goldsmith argues that for fair use to apply, the intended message of the derivative work expressly requires copying the original. 2 Live Crew’s “Pretty Woman” needed to copy the original Orbison song in order to comment on it. However, Warhol could have achieved his message about the celebrity and status of Prince without copying Goldsmith’s photo.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Goldsmith, it could have dramatic consequences for creators. It would create a higher standard for using another’s art as the basis of your own. Conversely, if the Court rules in favor of the Warhol Foundation, does that mean that courts must now be the arbiters of artistic meaning and whether it has been sufficiently transformed? Would artists with established fame and artistic bona fides benefit while lesser known artists would not?

If you have concerns about your works and their copyrights, contact Sprowls Law for a consultation.